October 1 2022 U.S.

Questions 1-10 are based on the following passage.

This passage is from Susan Vreeland, Clara and Mr. Tiffany. ©2011 by Susan Vreeland. The narrator is meeting with her former employer, Louis Comfort Tiffany, an artist whose company later became famous for designing stained glass lampshades.

“I’ve come to inquire if you have work for me. That is, if

my performance pleased you before.” A deliberate prompt. I

didn’t want to be hired because of my need or his kindness. I

wanted my talent to be the reason he wanted me back.

5 “Indeed” was all he offered.

What now to fill the suspended moment? His new

projects. I asked. His eyebrows leapt up in symmetrical

curves.

“A Byzantine chapel for the World’s Columbian

10 Exposition in Chicago next year. Four times bigger than the Paris Exposition Universelle. It will be the greatest assembly

of artists since the fifteenth century.” He counted on his fingers and then drummed them on the desk. “Only fifteen months away. In 1893 the name of Louis Comfort Tiffany

15 will be on the lips of millions!” He stood up and swung open his arms wide enough to embrace the whole world.

I sensed his open palm somewhere in the air behind the

small of my back, ushering me to his massive, carved

mahogany exhibit table to see his sketches and watercolors.

20“Two round windows, The Infancy of Christ and Botticelli’s Madonna and Child, will be set off by a dozen scenic side

windows.”

A huge undertaking. How richly fortunate. Surely there

would be opportunity for me to shine.

25 Practically hopping from side to side, he made a show of

slinging down one large watercolor after another onto the

Persian carpet, each one a precise, fine-edged rendering of

what he wanted the window to be.

“Gracious! You’ve been on fire. Go slower! Give me a

30 chance to admire each one.”

He unrolled the largest watercolor. “An eight-foot

mosaic behind the altar depicting a pair of peacocks

surrounded by grapevines.”

My breath whistled between my open lips. Above the

35 peacocks facing each other, he had transformed the

standard Christian icon of a crown of thorns into a

shimmering regal headdress for God the King, the thorns

replaced by large glass jewels in true Tiffany style.

Astonishing how he could get mere watercolors so deep

40 and saturated, so like lacquer that they vibrated together as

surely as chords of a great church pipe organ. Even the

names of the hues bore an exotic richness. The peacocks’

necks in emerald green and sapphire blue. The tail feathers

in vermilion, Spanish ocher, Florida gold. The jewels in the

45 crown mandarin yellow and peridot. The background in

turquoise and cobalt. Oh, to get my hands on those

gorgeous hues. To feel the coolness of the blue glass, like

solid pieces of the sea. To chip the gigantic jewels for the

crown so they would sparkle and send out shafts of light.

50 To forget everything but the glass before me and make of it something resplendent.

When I could trust my voice not to show too much

eagerness, I said, “I see your originality is in good health.

Only you would put peacocks in a chapel.”

55 “Don’t you know?” he said in a spoof of incredulity.

“They symbolized eternal life in Byzantine art. Their flesh

was thought to be incorruptible.”

“What a lucky find for you, that convenient tidbit of

information.”

60 He chuckled, so I was on safe ground.

He tossed down more drawings. “A marble-and-mosaic

altar surrounded by mosaic columns, and a baptismal font

of opaque leaded glass and mosaic.”

“This dome is the lid of the basin? In opaque leaded

65 glass?”

He looked at it with nothing short of love, and showed

me its size with outstretched arms as though he were

hugging the thing.

I was struck by a tantalizing idea. “Imagine it reduced in

70 size and made of translucent glass instead. Once you figure

how to secure the pieces in a dome, that could be the

method and the shape of a lampshade. A wraparound

window of, say”—I looked around the room—“peacock

feathers.”

75 He jerked his head up with a startled expression, the

idea dawning on him as if it were his own.

“Lampshades in leaded glass,” he said in wonder, his

blue eyes sparking.

“Just think where that could go,” I whispered.

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK

Questions 11-20 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Richard Florida, “Bigger Isn’t Necessarily Better When It Comes to City Size.” ©2017 by The Atlantic Monthly Group.

A pair of recent studies suggests that although

industrialized nations may have benefitted from larger

cities, the same is not true for the rapidly urbanizing areas of

the developing world. In these parts of the globe, there really

5 might be such a thing as too much urbanization, too

quickly.

The studies, by Susanne A. Frick and Andrés Rodríguez-

Pose of the London School of Economics, take a close look

at the actual connection between city size and nationwide

10 economic performance. Their initial study, from last year, examines the relationship between economic development,

as measured by GDP per capita, and average metropolitan-

area size in 114 countries across the world between 1960

and 2010. To ensure robustness, it controls for variables

15 including national population size, physical land area,

education levels, economic openness, and other factors.

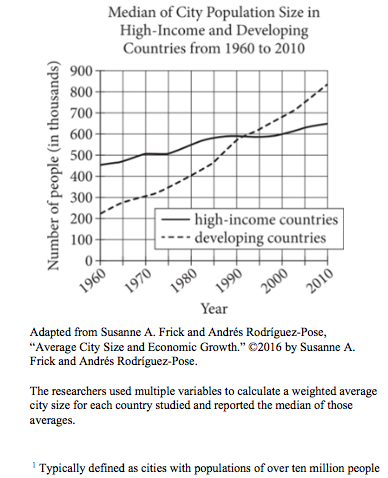

The size of cities or metro areas across the world has

exploded over the past half-century, with cities in the

developing world growing much faster and much larger

20 than those in more developed nations. Between 1960 and

2010, the median city in high-income countries grew

modestly from 500,000 to 650,000 people; but the median

city in the developing world nearly quadrupled, expanding

from 220,000 to 845,000 people. In 1960, 12 of the top 20

25 countries with the largest average city size were high-

income countries; by 2010, 14 of the top 20 were in the

developing world.

Urbanization has historically been thought of as a

necessary feature of economic development and growth, but

30 this study finds the connection is not so simple. While

advanced nations benefit from having larger cities,

developing nations do not. Advanced nations experience a

0.7 percent increase in economic growth for every

additional 100,000 in average population among its large

35 cities over a five-year period. But for developing nations, the addition of 100,000 people in large cities is associated with a

2.3 percent decrease in economic growth over a five-year

period.

In their latest study, the researchers found that

40 developing nations tend to get a bigger bang for their buck

from smaller and medium-size cities. These countries see

the most economic benefit from having a larger proportion

of their urban population living in cities of 500,000 people

or less. Bigger cities tend to have a more positive economic

45 impact in larger countries. Having a metro with more than

10 million inhabitants produces a nationwide economic

benefit only if the total urban population is 28.5 million

or more, according to the study. This makes sense:

Bigger, more developed countries are more likely to play

50 host to knowledge-based industries that require urban agglomeration economies.

There are several reasons why megacities1 often fail to

spur significant growth in the rapidly urbanizing world.

For one, the lion’s share of places that are urbanizing

55 most rapidly today are in the poorest and least-

developed parts of the world, whereas the places that

urbanized a century or so ago were in the richest and

most developed. This history has created a false

expectation that urbanization is always associated with

60 prosperity.

Additionally, globalization has severed the historical

connection between cities, local agriculture, and local

industry that powered the more balanced urban

economic development of the past. In today’s globally

65 interconnected economy, the raw materials that flowed

from the surrounding countryside to the city can all be

inexpensively imported from other parts of the world.

The result is that the connection between large cities and

growth has now become much more tenuous, producing

70 a troubling new pattern of “urbanization without

growth.”

Questions 21-31 are based on the following passages.

Passage 1 is adapted from “Humans’ Big Brains May Be Partly due to Three Newly Found Genes.” ©2018 by Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. Passage 2 is adapted from Matt Wood, “Brain Size of Human Ancestors Evolved Gradually over 3 Million Years.” ©2018 by The University of Chicago Medical Center.

Passage 1

The brains of humans are conspicuously larger than the

brains of other apes, but the human-specific genetic

factors responsible for the uniquely large human

neocortex remain obscure. Since humans split from

5 chimps, which have brains roughly a third of human size,

the human genome has undergone roughly 15 million

changes. Which of these genetic tweaks could have led to

big brains?

About six years ago, scientists in David Haussler’s lab at

10 Howard Hughes Medical Institute discovered a gene called

NOTCH2NL. It’s a relative of NOTCH2, a gene that

scientists knew was central to early brain development.

NOTCH2 controls vital decisions regarding when and how many neurons to make.

15 When the Haussler team looked in the official version

of the human genome at that time1—version 37—

NOTCH2NL appeared to be located in chromosome 1

near a region linked to abnormal brain size. Delete a hunk

of the region, and brains tend to shrink. Duplicate part of

20 it, and brains tend to overgrow.

“We thought, ‘Oh, this is incredible,’” Haussler said.

NOTCH2NL seemed to check all the boxes for a key role

in human brain development. But when the team mapped NOTCH2NL’s precise location in the genome, they

25 discovered the gene wasn’t actually in the relevant

chromosomal region after all; the once-promising

candidate seemed to be a dud.

“We were downhearted,” Haussler recalled. That all

changed with the next official version of the human

30 genome—version 38. In this iteration, NOTCH2NL was

located in the crucial region. “And there were three

versions of it,” Haussler exclaimed. Over the last three

million years, his team calculated, NOTCH2NL was

repeatedly copy-pasted into the genome, what he calls “a

35 series of genetic accidents.”

Genetic analysis of several primate species revealed that

the three genes exist only in humans and their recent

relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans, not in

chimpanzees, gorillas, or orangutans. What’s more, the

40 timing of these genes’ emergence matches up with the

period in the fossil record when our ancestors’ craniums

began to enlarge, Haussler points out. Together, the results

suggest that NOTCH2NL genes played a role in beefing

up human brain size.

Passage 2

45 Modern humans have brains that are more than three

times larger than our closest living relatives,

chimpanzees and bonobos. Scientists don’t agree on

when and how this dramatic increase took place, but

new analysis of 94 hominin fossils shows that average

50 brain size increased gradually and consistently over the

past three million years.

The research, published in The Proceedings of the

Royal Society B, shows that the trend was caused

primarily by evolution of larger brains within

55 populations of individual species, but the introduction of

new, larger-brained species and extinction of smaller-

brained ones also played a part.

“Brain size is one of the most obvious traits that

makes us human. It’s related to cultural complexity,

60 language, tool making and all these other things that

make us unique,” said Andrew Du, PhD, a postdoctoral

scholar at the University of Chicago and first author of

the study. “The earliest hominins had brain sizes like

chimpanzees, and they have increased dramatically since

65 then. So, it’s important to understand how we got here.”

Du and his colleagues compared published research

data on the skull volumes of 94 fossil specimens from 13

different species, beginning with the earliest

unambiguous human ancestors, Australopithecus, from

70 3.2 million years ago to pre-modern species, including

Homo erectus, from 500,000 years ago when brain size

began to overlap with that of modern-day humans.

The researchers saw that when the species were

counted at the clade level, or groups descending from a

75 common ancestor, the average brain size increased

gradually over three million years. Looking more closely,

the increase was driven by three different factors,

primarily evolution of larger brain sizes within

individual species populations, but also by the addition

80 of new, larger-brained species and extinction of smaller-

brained ones.

The study quantifies for the first time when and by

how much each of these factors contributes to the clade-

level pattern. Du said he likens it to how a football coach

85 might build a roster of bigger, strong players. One way

would be to make all the players hit the weight room to

bulk up. But the coach could also recruit new, larger

players and cut the smallest ones.

1The reference version of the human genome goes through updates to more completely map out each chromosomal sequence.

Questions 31-41 are based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from a speech delivered by Tom Calma, “Still Riding for Freedom.” ©2008 by Australian Human Rights Commission. Aboriginal Australians and the Torres Strait Islanders are the indigenous peoples of Australia.

For too long now, we have heard it argued that a focus

on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights

takes away from a focus on addressing Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples’ disadvantage.

5 This approach is, in my view, seriously flawed for a

number of reasons. It represents a false dichotomy—as if

poorer standards of health, lack of access to housing,

lower attainment in education and higher unemployment

are not human rights issues or somehow they don’t relate

10 to the cultural circumstances of Indigenous peoples.

And it also makes it too easy to disguise any causal

relationship between the actions of government and any

outcomes, and therefore limits the accountability and responsibilities of government.

15 In contrast, human rights give Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples a means for expressing their

legitimate claims to equal goods, services, and most

importantly, the protections of the law—and a standard

that government is required to measure up to.

20 The focus on ‘practical measures’ was exemplified by

the emphasis the previous federal government placed on

the ‘record levels of expenditure’ annually on Indigenous

issues.

As I have previously asked, since when did the size of

25 the input become more important than the intended

outcomes? The . . . government never explained what the

point of the record expenditure argument was—or what achievements were made. . . .

And the fact is that there has been no simple way of

30 being able to decide whether the progress made through

‘record expenditure’ has been ‘good enough’. So the

‘practical’ approach to these issues has lacked any

accountability whatsoever. . . .

If we look back over the past five years in particular . . .

35 we can also see that a ‘practical’ approach to issues has

allowed governments to devise a whole series of policies

and programs without engaging with Indigenous peoples

in any serious manner. I have previously described this as

the ‘fundamental flaw’ of the federal government’s efforts

40 over the past five years. That is, government policy that is

applied to Indigenous peoples as passive recipients.

Our challenge now is to redefine and understand these

issues as human rights issues.

We face a major challenge in ‘skilling up’ government

45 and the bureaucracy so that they are capable of utilising

human rights as a tool for best practice policy

development and as an accountability mechanism.

. . . In March this year, the Prime Minister, the Leader

of the Opposition, Ministers for Health and Indigenous

50 Affairs, every major Indigenous and non-Indigenous

peak health body and others signed a Statement of Intent

to close the gap in health inequality which set out how

this commitment would be met. It commits all of these

organisations and government, among other things, to:

- 55 develop a long-term plan of action, that is targeted

to need, evidence-based and capable of addressing

the existing inequities in health services, in order to

achieve equality of health status and life expectancy

between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

60 peoples and non-Indigenous Australians by 2030. - ensure the full participation of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples and their

representative bodies in all aspects of addressing

their health needs. - 65 work collectively to systematically address the social

determinants that impact on achieving health

equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples. - respect and promote the rights of Aboriginal and

70 Torres Strait Islander peoples, and - measure, monitor, and report on our joint efforts,

in accordance with benchmarks and targets, to

ensure that we are progressively realising our

shared ambitions.

75 These commitments were made in relation to

Indigenous health issues but they form a template for the

type of approach that is needed across all areas of

poverty, marginalisation and disadvantage experienced

by Indigenous peoples.

80 They provide the basis for the cultural shift necessary

in how we conceptualise human rights in this country.

Issues of entrenched and ongoing poverty and

marginalisation of Indigenous peoples are human rights

challenges. And we need to lift our expectations of what

85 needs to be done to address these issues and of what

constitutes sufficient progress to address these issues in

the shortest possible timeframe so that we can realise a

vision of an equal society.

Questions 42-52 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

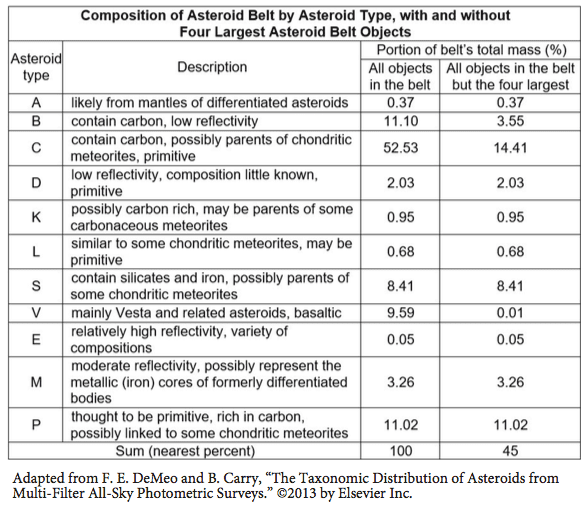

This passage is adapted from John Chambers and Jacqueline Mitton, From Dust to Life: The Origin and Evolution of Our Solar System. ©2014 by John Chambers and Jacqueline Mitton. Differentiated asteroids are made up of layers of different material, such as an iron core, a rocky mantle, and a thin volcanic crust. Primitive asteroids are undifferentiated asteroids that are thought to have changed little since they formed.

Scientists believe that iron meteorites come from

the cores of asteroids that melted. But what happened

to the corresponding rocky material that formed the

mantles of these bodies? A few asteroids have spectra1

5 that match those of mantle rocks, but they are very

rare. Some nonmetallic meteorites come from

asteroids that have partially or wholly melted, but

these do not match the minerals we would expect to

see in the missing mantles of the iron parent bodies.

10 These exotic meteorites must come from some other

kind of parent body instead.

The rarity of mantle rocks in our meteorite

collection and in the asteroid belt, known as the

“missing mantle problem,” is a long-standing puzzle.

15 There are several reasons why iron fragments might

survive better than rocky fragments when asteroids

break apart. Iron lies in the core of a differentiated

asteroid, while rocky material lies near the surface.

Thus, rocky material will be the first to be removed

20 when an asteroid is bombarded, while iron is the last

to be exposed. As a result, rocky fragments have to

survive in space for longer than iron ones. Most of the

rocky mantle may be peeled away in small fragments

—chips from the surface—while the iron core remains

25 as a single piece, making it harder to disrupt later. Last

and most important, iron is much stronger than rock:

a piece of iron is likely to survive in the asteroid belt at

least 10 times longer than a rocky fragment of the

same size.

If most differentiated bodies broke apart early in

the solar system, perhaps all the mantle material has

been ground down to dust and lost over the billions of

years since then. This would mean that intact

differentiated asteroids are very rare in the asteroid

belt today. Perhaps Vesta [a differentiated asteroid

with a diameter of more than 300 miles] and a handful

of others are all that remain.

However, collisional erosion cannot be the whole

story. Primitive asteroids, the parent bodies of

40 chondritic meteorites [the most common type of

meteorite found on Earth], are no stronger than the

mantle rocks from differentiated asteroids. How did

so many primitive asteroids survive when almost

none of the differentiated ones did? Part of the

45 explanation may simply be that differentiated bodies

were relatively rare to begin with and none have

survived. Still, if almost all differentiated bodies were

destroyed in violent collisions, how did Vesta survive

with only a single large crater on its surface?

Astronomer William Bottke and his colleagues

recently came up with a possible explanation: perhaps

the parent bodies of the iron meteorites formed closer

to the Sun, in the region that now contains the

terrestrial planets. Objects would have been more

55 tightly packed nearer the Sun, so collisions would

have been more frequent than in the asteroid belt.

Many, perhaps most, differentiated bodies were

disrupted by violent collisions. Gravitational

perturbations from larger bodies scattered some of

60 these fragments into the asteroid belt. Both iron and

rocky fragments arrived in the asteroid belt, but only

the stronger iron objects have survived for the age of

the solar system. Later on, the parent bodies of

primitive meteorites formed in the asteroid belt. Most

65 of these objects survived, leaving an asteroid belt

today that is a mixture of intact primitive bodies and

fragments of iron.

1 Characteristic wavelengths of light that asteroids reflect.

Writing and Language Test

Questions 1-11 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

The Lemur's Unique Traits

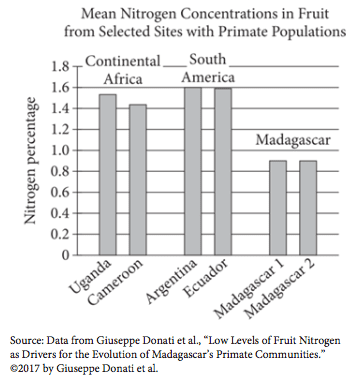

The often striped tail of the lemur, a primate found only on the island nation of Madagascar, is just one of this animal’s unique qualities. While most primates eat only during the day, the lemur eats during the day and at night, 1 and while most primates primarily eat fruit, the lemur primarily eats leaves. A 2017 study conducted by an international team of scientists 2 suggest that a lack of nitrogen in Madagascar’s fruits may have caused the lemur to develop these unusual feeding traits through evolution.

Nitrogen, a key element found in all proteins, is one of the most important factors in any animal’s 3 survival. It is important because proteins are used for functions such as building muscle and moving oxygen through the bloodstream. Many primates 4 obtain a large proportion of their dietary nitrogen from fruit, so the researchers suspected that Madagascar’s fruit had insufficient levels of nitrogen for the lemur; without it, lemurs’ bodies cannot synthesize enough protein to live. To get an answer, the scientists tested the levels of nitrogen in fruit from multiple primate habitats.

Sites were chosen in continental 5 Africa; South America, and Madagascar because primate families in these locations all have the same relative nitrogen requirements. At the continental African sites in Uganda and Cameroon, 6 however, the scientists found fruit to have nitrogen concentrations of 1.53 percent and 1.44 percent, respectively. The South American sites yielded similar results, with nitrogen concentrations in fruit

of 1.60 percent in 7 Ecuador and 1.30 percent in Argentina. Madagascar’s levels, however, were lower:

8 fruit selected from one site there showed a nitrogen concentration of only 0.6 percent. Although it remains unclear if primates in areas other than Madagascar acquire all the nitrogen they need by eating fruit, the researchers knew from prior studies that fruit with a nitrogen concentration of 0.9 percent is below the minimum amount of nitrogen (1.1 percent) that a primate requires.

[1] These data indicated to scientists that the lower levels of nitrogen in Madagascar’s fruit 9 likely forced the lemurs to start eating nitrogen-rich leaves so that their bodies could synthesize protein. [2] In addition, the lemur’s tendency to eat both day and night may be an adaptation it developed due to limited nitrogen: lemurs may need to eat for more hours per day to meet their dietary needs. [3] As Abigail Derby Lewis, one of the 10 studies’ ecologists’, says, “Knowing how and why they evolved in the direction they have—from their diet, to social structure and cognition—is crucial in helping to inform effective conservation approaches.” 11

Questions 12-22 are based on the following passage.

Bicycling in the Netherlands

Approximately 22,000 miles of bicycle paths crisscross the Netherlands, making cycling in and between Dutch cities safe and convenient. In fact, according to the European Cyclists’ Federation, the Netherlands is one of the two most bike friendly countries in Europe (sharing top honors with Denmark). While the Netherlands is well known as a cycling hub, less well known is how 12 was that reputation earned? Persistent activism over many years was instrumental to the enduring popularity of cycling among the Dutch.

In the early twentieth century, the Dutch were cycling 13 enthusiasts, not only riding but also manufacturing bicycles in large numbers. Cycling made sense in the flat, densely populated country. As personal income grew in the postwar boom years of the 1950s and 1960s, 14 in short, car ownership rose sharply, and cars began to eclipse bikes in popularity. Along with more cars came an alarming spike in traffic accidents on narrow streets not designed to accommodate large numbers of cars. 15

[1] By the 1970s, concerned citizens started organizing demonstrations to promote safety for cyclists and pedestrians. [2] They declared car-free holidays, closing off streets and hosting street parties. [3] They organized mass bike rides. [4] They wrote protest songs and serenaded the prime minister outside his 16 resident’s. [5] Tom Godefrooij, a longtime member of the Dutch Cyclists’ 17 Union (Fietsersbond), recalls that the activists’ efforts often led to good publicity. [6] “We had a great fighting spirit and we knew how to voice our ideas,” he recounted in a 2015 interview. 18

As the 1980s approached, local governments began to respond to the demonstrations by Fietsersbond and other groups by funding projects to improve the nation’s cycling 19 infrastructure. As a result of the improved infrastructure, more people were encouraged to use bicycles as their primary means of transportation. The improvements made cycling easier and safer. 20 Some funding came from private donors. Bike lanes and racks appeared on city streets, many of which featured speed bumps and turns that forced cars to drive 21 more slowly than they would on streets without those features and to yield.

Promoting cycling continues to be a national priority in the twenty-first century, and the Dutch government often partners with cycling organizations to craft policies that improve access and safety for cyclists. But challenges remain. Fietsersbond, now more than 34,000 members 22 of strongness, continues to advocate for the cycling community. “The battle goes on,” says Godefrooij. “We’ve come a long way, but we can never lower our guard.”

Questions 23-33 are based on the following passage.

The Mysterious Women of Delirious Matter

Discussing her 2018 sculpture installation Delirious Matter with a reporter, Diana Al-Hadid 23 made a statement about art’s “old masters.” She stated that these artists, who were exclusively men, often portrayed women as “either encased in a giant pile of fabric or lounging horizontally.” To Al-Hadid, 24 they reveal a lot about the role of women in precontemporary art:

25 women were goddesses, objects of desire, or both. In her own installation, she asks viewers to reassess these stereotypical representations, particularly classical Greek and Roman ones, through her clever use of abstractions and visual illusions.

These techniques are displayed vividly in Delirious Matter’s three life-size female figures, which, like many classical Greek sculptures of women, are seated or lying down as if waiting for someone. The figures are headless, an abstraction that echoes famous ancient works such as the armless statue Venus de Milo and emphasizes the centrality of the body (over the mind) in traditional sculptures of women. 26 Rather, the figures are incomplete shells, which Al-Hadid constructed by pouring a gypsum-polymer mixture over a mold of a female form, letting the mixture drip down in streaks, and then 27 the mold was removed. Many of the solidified streaks do not connect, 28 allowing viewers to see through the figures, creating the illusion that they are intangible. Finally, the plinths the figures rest on are also made of isolated, incomplete streaks, giving the impression that the figures are floating in midair.

29 A female figure is depicted in Delirious Matter’s similarly drippy, lacelike, 14-foot-tall sculpture Gradiva, which alludes to Wilhelm Jensen’s 1902 novella of the same name. In the novella, a male archaeologist becomes so infatuated with the “maidenly grace” of a well-known Roman sculpture of a woman, whom he calls Gradiva, that he begins to hallucinate that she is alive. The archaeologist’s idealizations of and delusions about Gradiva are represented in Al-Hadid’s wall-like sculpture: its disconnected streaks make it hard for viewers to identify the subtle image of Gradiva. By obscuring the image, Al-Hadid 30 asks viewers of the image to wonder whether or not they are actually seeing Gradiva. This formlessness of Al-Hadid’s Gradiva then points to the limitations of the Roman Gradiva: she was a fantasy, unrealistic and objectified. 31 Wasn’t there more to the Roman woman than her “maidenly grace.”

Although the fact that Delirious Matter’s sculptures are fragmentary and porous 32 create the illusion that they are delicate objects, it also suggests that their female subjects have escaped to transcend their original forms. If the women have 33 escaped, perhaps it is to take their places as viewers, or even as the artist herself.

Questions 34-44 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Kitchen Incubators: Cooking Up Opportunities

—1 —

Kitchen incubators, as the term suggests, help establish and nurture new food businesses. In exchange for 34 unimportant fees, kitchen incubators provide would-be entrepreneurs with the facilities, training, and customers they need to succeed. 35 Anyone, interested in starting a food business, would be wise to consider working with a kitchen incubator.

—2 —

While the cost of building and equipping a commercial kitchen is prohibitive for most new businesses, incubators offer their members the use of fully equipped kitchens at affordable hourly rates. At Micro Mercantes in Portland, Oregon, for instance, 36 there is a tortilla press, a rice cooker, and a variety of pots and pans. The kitchen facilities are in use more than 150 hours per week. High demand for kitchen space at Micro Mercantes and other incubators demonstrates that entrepreneurs value this service.

—3 —

Kitchen incubators also assist business owners by offering classes on subjects such as food safety, budgeting, and recipe scaling. Maria Lizama credits Micro Mercantes classes with preparing her to open a food truck from which to sell pupusas, a traditional dish of her native El Salvador. The training she received at Micro Mercantes helped Lizama in many aspects of her business, including 37 the aspect of developing a marketing plan and hiring the right employees.

—4 —

Many kitchen incubators provide access to another necessary component of a 38 successful—business— customers. For example, Hope & Main, based in Warren, Rhode Island, hosts a market where customers try free samples of treats like pralines, pimento cheese, and rugelach—all made by vendors using the incubator’s kitchens—before they buy. Hope & Main’s founder and president Lisa Raiola says customers provide valuable feedback to vendors. “We have had many companies crowdsource and perfect their recipes, packaging, and branding,” she explains.

—5 —

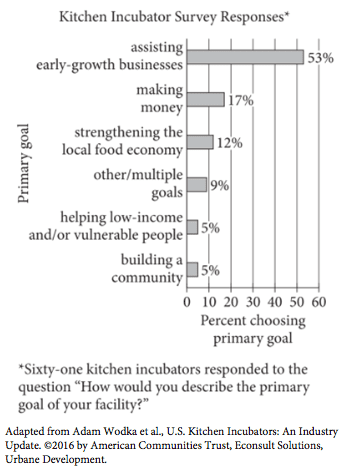

The growth of kitchen incubators is a testament to 39 its importance to burgeoning small businesses. A 2016 industry report notes that the number of kitchen incubators increased more than 50% from 2013 to 2016. A survey published in the report shows that most incubators surveyed (53%) 40 experienced growth during that time. While profits were paramount to 17% of incubators, others indicated that strengthening the local food economy (12%), helping people in need (5%), and building community (5%) were primary concerns.

—6 —

The food industry is very competitive, and 41 consumers’ tastes are notoriously fickle. 42 In addition, entrepreneurs who make the small monetary investment that kitchen incubators require find 43 them and their fledgling food businesses well positioned to succeed.

Leave a Reply